As generative AI systems advance, so too does their appetite for energy. Training and running large language models consumes vast amounts of electricity. AI’s energy demand is projected to double in the next five years, gobbling up 3 percent of total global electricity consumption. But what if AI chips could function more like the human brain, processing complex tasks with minimal energy? A growing chorus of scientists and engineers believes that the key might lie in organoid intelligence.

AI enthusiasts were introduced to the concept of brain-inspired chips in July at the United Nations’ AI for Good Summit in Geneva. There, David Gracias, a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at Johns Hopkins University, gave a talk discussing the latest research he’s led on biochips and their applications to AI. Focused on nanotech, intelligent systems, and bioengineering, Gracias’s research team is among the first to build a functioning biochip that combines neural organoids with advanced hardware, enabling chips to run on and interact with living tissue.

Organoid intelligence is an emerging field that blends lab-grown neurons with machine learning to create a new form of computing. (The term ‘organoid intelligence’ was coined by Johns Hopkins researchers including Thomas Hartung.) The neurons, called organoids, are more specifically three-dimensional clusters of lab-grown brain cells that mimic neural structures and functions. Some researchers believe that so-called biochips—organoid systems that integrate living brain cells into hardware—have the potential to outstrip silicon-based processors like CPUs and GPUs in both efficiency and adaptability. If commercialized, experts say biochips could potentially reduce the staggering energy demands of today’s AI systems while enhancing their learning capabilities.

“This is an exploration of an alternate way to form computers,” Gracias says.

How Do Biochips Mimic the Brain?

Traditional chips have long been confined to two-dimensional layouts, which can limit how signals flow through the system. This paradigm is starting to shift, as chipmakers are now developing 3D chip architectures to increase their devices’ processing power.

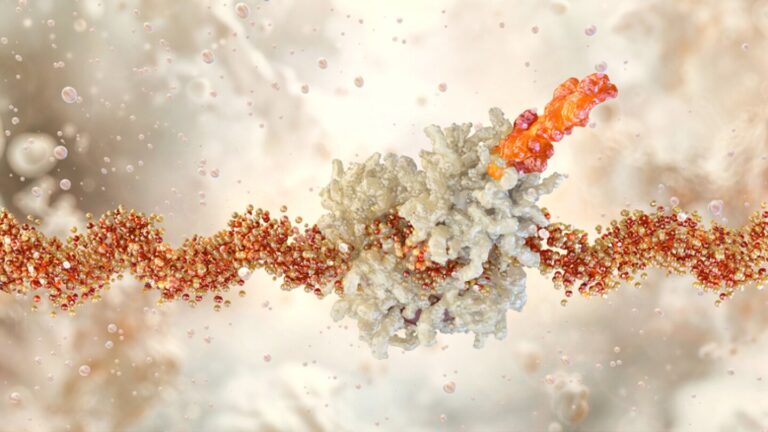

Similarly, biochips are designed to emulate the brain’s own three-dimensional structure. The human brain can support neurons with up to 200,000 connections—levels of interconnectivity Gracias says flat silicon chips can’t achieve. This spatial complexity allows biochips to transmit signals across multiple axes, which could enable more efficient information processing.

Gracias’s team developed a 3D electroencephalogram (EEG) shell that wraps around an organoid, enabling richer stimulation and recording than conventional flat electrodes. This cap conforms to the organoid’s curved surface, creating a better interface for stimulating and recording electrical activity.

To train organoids, the team uses reinforcement learning. Electrical pulses are applied to targeted regions. When the resulting neural activity matches a desired pattern, it’s reinforced with dopamine, the brain’s natural reward chemical. Over time, the organoid learns to associate certain stimuli with outcomes.

Once a pattern is learned, it can be used to control physical actions, such as steering a miniature robot car through strategically placed electrodes. This demonstrates neuromodulation—the ability to produce predictable responses from the organoid. These consistent reactions lay the groundwork for more advanced functions, such as stimulus discrimination, which is essential for applications like facial recognition, decision-making, and generalized AI inference.

Gracias’s team is in the early stages of developing miniature self-driving cars controlled by biochips: A proof of concept that the system can act as a controller. This experimental work suggests future roles in robotics, prosthetics, and bio-integrated implants that communicate with human tissue.

These systems also hold promise in disease modeling and drug testing. Gracias’s group is developing organoids that mimic neurological diseases like Parkinson’s. By observing how these diseased tissues respond to various drugs, researchers can test new treatments in a dish rather than relying solely on animal models. They can also uncover potential mechanisms of cognitive impairment that current AI systems fail to simulate.

Because these chips are alive, they require constant care: temperature regulation, nutrient feeding, and waste removal. Gracias’s team has kept integrated biochips alive and functional for up to a month with continuous monitoring.

Fred Jordan (left) Martin Kutter are the founders of FinalSpark, a Swiss startup developing biochips that the company claims can store data in living neurons.FinalSpark

Fred Jordan (left) Martin Kutter are the founders of FinalSpark, a Swiss startup developing biochips that the company claims can store data in living neurons.FinalSpark

Challenges in Scaling Biochip Technology

Yet significant challenges remain. Biochips are fragile and high maintenance, and current systems depend on bulky lab equipment. Scaling them down for practical use will require biocompatible materials and technologies that can autonomously manage life-supporting functions. Neural latency, signal noise, and the scalability of neuron training also present hurdles for real-time AI inference.

“There are a lot of biological and hardware questions,” Gracias says.

Meanwhile, some companies are testing the waters. Swiss startup FinalSpark claims its biochip can store data in living neurons—a milestone it calls a “bio bit,” says Ewelina Kurtys, a scientist and strategic advisor at the company. This step suggests biological systems could one day perform core computing functions traditionally handled by silicon hardware.

FinalSpark aims to develop remote-accessible bioservers for general computing in about a decade. The goal is to match digital processors in performance while being exponentially more energy-efficient. “The biggest challenge is programming neurons, as we need to figure out a totally new way of doing this,” Kurtys says.

Still, transitioning from the lab to industry will require more than just technical breakthroughs. ”We have enough funding to keep the lab running,” Gracias says. “But for the research to take off, more funding is needed from Silicon Valley.”

Whether biochips will augment or replace silicon remains to be seen. But as AI systems demand more and more power, the idea of chips that think—and sip energy—like brains is becoming increasingly attractive.

For Gracias, that technology could be shipped to market sooner than we think. “I don’t see any major show stoppers on the way to implementing this,” he says.

Fred Jordan (left) Martin Kutter are the founders of FinalSpark, a Swiss startup developing biochips that the company claims can store data in living neurons.FinalSpark

Fred Jordan (left) Martin Kutter are the founders of FinalSpark, a Swiss startup developing biochips that the company claims can store data in living neurons.FinalSpark