Imagine a future in which farmers can tell when plants are sick even before they start showing symptoms. That ability could save a lot of crops from disease and pests—and potentially save a lot of money as well.

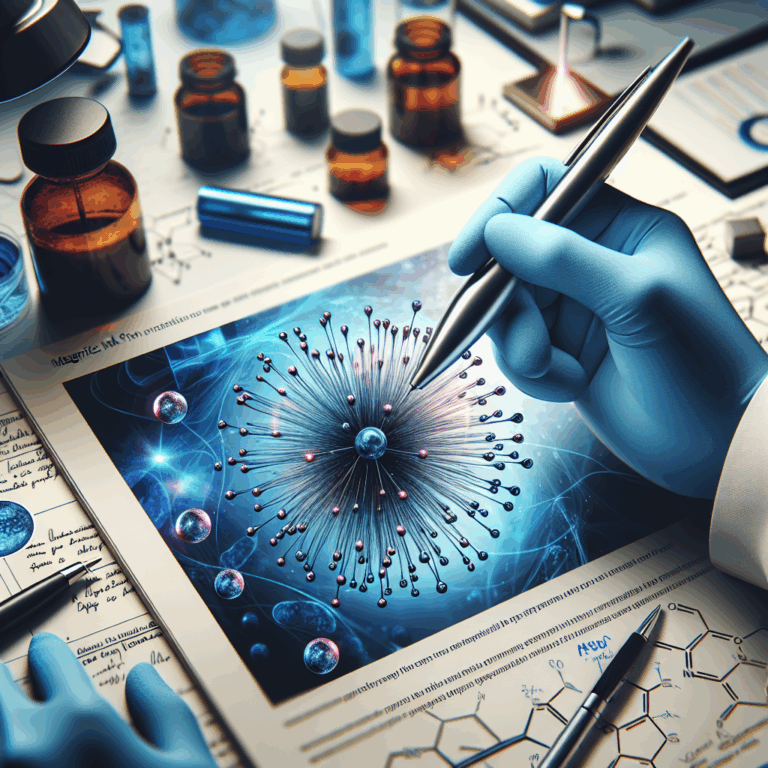

A team of researchers in Singapore and China have taken a step toward that possibility with their development of ultrathin electronic tattoos—dubbed e-tattoos—to study plant immune responses without the need for piercing, cutting, or bruising leaves.

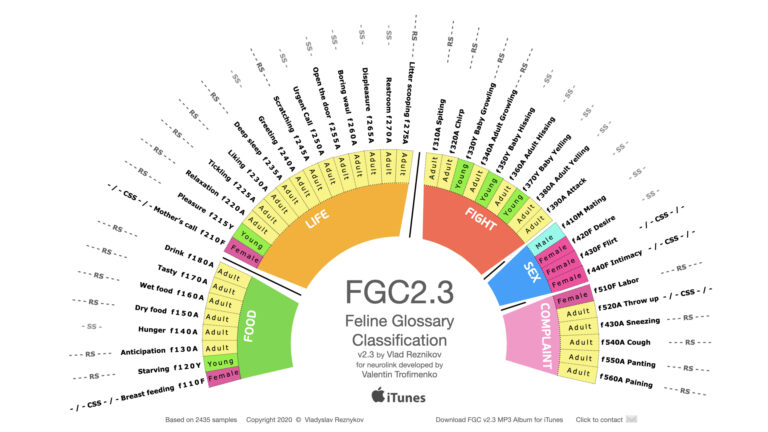

The e-tattoo is a silver nanowire film that attaches to the surface of plant leaves. It conducts a harmless alternating current—in the microampere range—to measure a plant’s electrochemical impedance to that current. That impedance is a telltale sign of the plant’s health.

Lead author Tianyiyi He, an associate professor of the Shenzhen MSU-BIT University’s Artificial Intelligence Research Institute, says that a healthy plant has a characteristic impedance spectrum—it’s as unique to the plant as a person’s fingerprints. “If the plant is stressed or its cells are damaged, this spectrum changes in shape and magnitude. Different stressors—dehydration, immune response—cause different changes.”

This is because plant cells, He explains, are like tiny chambers with fluids passing through them. The membranes of plant cells act like capacitors, resisting the flow of electrical current. “When cells break down—like in an immune response—the current flows more easily, and impedance drops,” He adds.

Detecting Plant Stress Early with E-Tattoos

Different problems yield different electrical responses: Dehydration, for example, looks different than an infection. Changes in a plant’s impedance spectrum means that something is not right—and by looking at where and how that spectrum changed, He’s team could spot what the problem was, up to three hours before physical symptoms started appearing.

The researchers conducted the work in a controlled environment. He says that a lot more research is needed to help scientists spot a wider array of responses to stressors in the real-world environment. But this is a good step in that direction, says Eleni Stavrinidou, principal investigator in the electronic plants research group from Linköping University’s Laboratory of Organic Electronics in Sweden, who was not involved in the work. He’s team published its work on 4 April in Nature Communications.

The team tested the film on lab-grown thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana) for 14 days. They mixed the nanowires in water so that they could transfer smoothly to the plant, by simply dripping the mix onto the leaves. Then they applied the e-tattoo in two different positions—side by side on a single leaf and on opposite faces of a leaf—to see how the current would flow. Then, with a droplet of galistan (a liquid metal alloy composed of gallium, indium, and tin), they attached a copper wire with the diameter of a human hair to the e-tattoo’s surface to apply an AC current from a small generator. He’s team collected data every day to see how plants would react.

Control plants showed a consistent spectrum over the course of two weeks, but plants that received immune-response stimulants (such as ethanol) or were wounded or dehydrated showed different patterns of electrical impedance spectra.

He says liquid-carried silver nanowires worked better than other highly conductive metals such as copper or nickel because they were not soft enough to entirely “glue” to plants’ leaves and stay perfectly plastered even as the leaf bends or wrinkles. And in the case of thale cresses, they also have tricomas, tiny hairlike structures that usually protect and keep leaves from losing too much water. Tricomas, He explains, hinder perfect attachment since they make a leaf’s surface uneven—but silver nanowires managed to get around the problem in a better way than other materials.

“Even the smallest gaps between the film and the leaf can mess with electrical impedance spectroscopy readings,” He says.

The silver nanowire e-tattoo proved to be versatile, too. It also worked with coleus, polka-dot plants, and benth—a close relative to tobacco, field mustard, and sweet potato. The team noticed the material did not block sun rays, which means it did not interfere with photosynthesis.

Advancements in Plant Impedance Spectroscopy

This isn’t the first time tattoos or electrical impedance spectroscopy have been used for plants, says Stavrinidou.

What’s new in the study, Stavrinidou says, “is the validation—they show this approach works on delicate plants like Arabidopsis and links clearly to immune responses.”

Stavrinidou says that ensuring that impedance spectrum changes tell exactly what is wrong with a plant in an unknown scenario is still a challenge. “But this paper is a strong step in that direction.”

At scale, the technique could be another tool to help farmers spot problems in their crops. But the technique will need improvement to get there, He says. Researchers can, for example, redesign the circuits to optimize them. “We can further shrink it to smaller sizes and add wireless communication to build IoT (Internet of Things) systems so we don’t have to link every plant to a wire. Everything is going to be wireless, connected, and transmitted to the cloud,” He says.

To Stavrinidou, this work is a step toward a long-term goal: the development of sensors that correlate biological signals to physiological states—stress, disease, or growth—non-invasively.

“As more of these studies are done, we’ll be able to map out what different impedance signals mean biologically. That opens the door to sensors that are not just diagnostic, but predictive—a game-changer for agriculture,” Stavrinidou says.