A team of Swiss researchers has improved the walking ability of two people with long-standing spinal cord injuries (SCI) using deep brain stimulation (DBS), which excites neurons with surgically implanted electrodes in the brain.

Investigators targeted a surprising brain region: the lateral hypothalamus, which is associated with a variety of basic functions, though not especially with locomotion. A paper detailing the human pilot study and underlying animal research, which led the researchers to the lateral hypothalamus, was published last week in Nature Medicine. Many of the researchers involved in the study hail from the NeuroRestore Lab affiliated with the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (EPFL), which has previously done extensive work on restoring walking with electrodes implanted in the spinal cord.

The new study is attracting attention. “This is really a tour de force,” says Christopher Butson, a biomedical engineer at the University of Florida, which hosts an annual Deep Brain Stimulation Think Tank. “It seems amazingly thorough.”

“It could have been ten papers,” said Nestor Tomycz, a neurosurgeon with the Allegheny Health Network and Drexel University, who routinely treats motor-related diseases, such as Parkinson’s, with DBS. He also called it a “tour de force,” with implications in fields such as neurosurgery, neurobiology, brain mapping, and rehabilitation.

An Unexpected Brain Target

The research didn’t begin with the lateral hypothalamus in mind. “Instead of looking at individual targets, the technique we have used considered all possible brain regions and statistically highlighted the regions that underwent anatomical and functional changes following SCI,” said Léonie Asboth, a study co-author and clinical research director at Lausanne University Hospital.

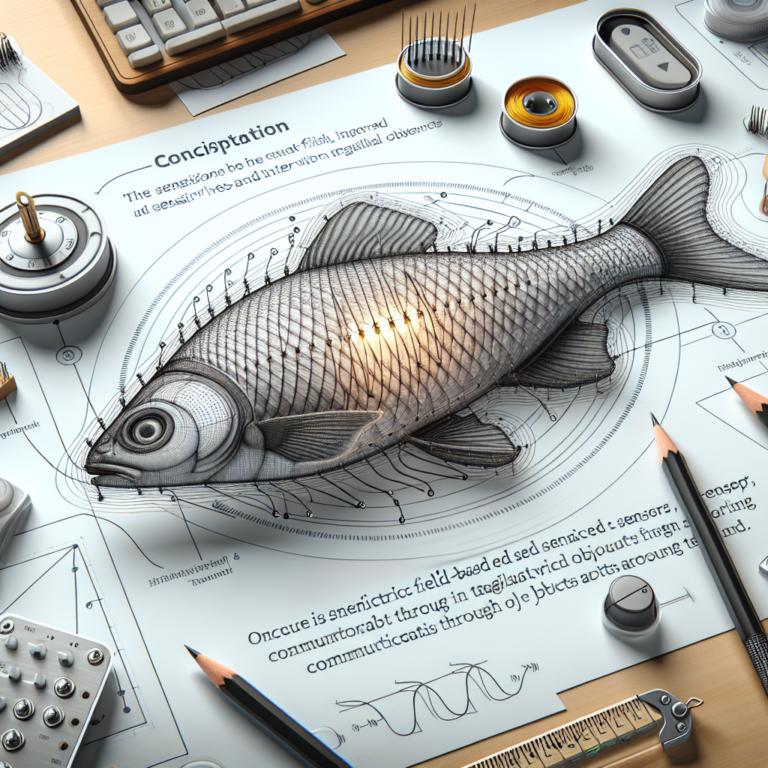

Following a spinal cord injury classified as incomplete, some communication between the brain and extremities is preserved, and some degree of natural recovery of walking ability is not uncommon in mice or humans. The researchers set out to learn which parts of the brain might be most active in that recovery.

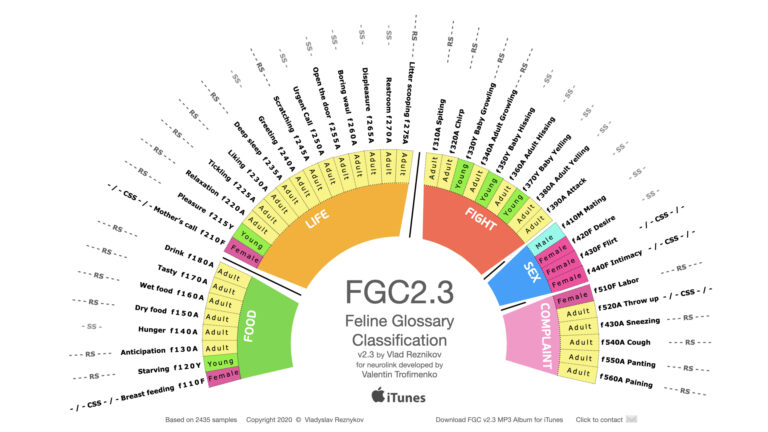

The team looked at the brains of injured mice soon after injury and again after eight weeks, comparing them to the brains of uninjured mice to create a “brain atlas” of locomotion recovery. This mapping left the team with one prime candidate: the lateral hypothalamus. This brain region is typically associated with a variety of bodily functions and behaviors, including “feeding, motivation, reward processing, and arousal,” said Asboth.

Stimulating the lateral hypothalamus in both injured mice and rats improved walking recovery, leading to an attempt at translating the treatment to human patients. “Prior studies had already explored DBS in the hypothalamus for other conditions, such as cluster headaches and refractory obesity, providing sufficient safety data as a foundation for its use in this context,” said Asboth.

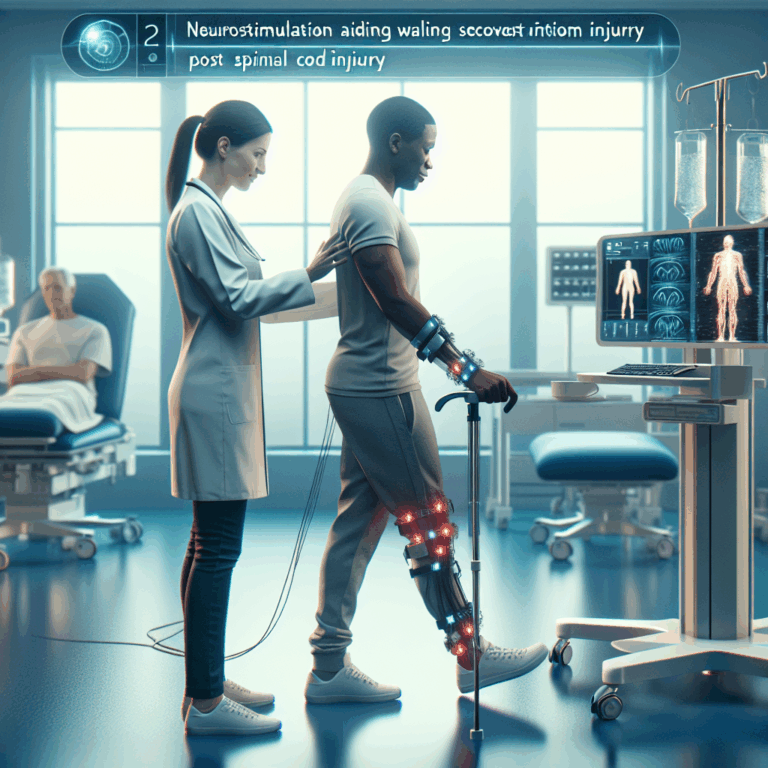

Deep brain stimulation enabled a man with an incomplete spinal cord injury to climb stairs. NPG Press/YouTube

A Pilot Study in Humans

The study used commercially available deep brain stimulation technology from Medtronic, taking advantage of decades of research behind equipment and surgical techniques. After receiving the implant one patient reportedly said, “I feel the urge to move my legs.”

A pair of patients, both with incomplete spinal cord injuries, then used DBS throughout a three-month rehabilitation program with about nine hours of training per week. Walking ability improved immediately with DBS turned on, with positive results following treatment even with the electrodes turned off. Notably, with DBS, both participants were able to walk without braces and navigate stairs independently. No serious side effects were reported.

“It’s surprising they could achieve something that is so specific,” said Butson—that is, improved locomotion recovery, without any side effects related to other functions of the lateral hypothalamus or surrounding brain areas.

Both patients, years removed from their initial injuries, were beyond the conventional recovery period, and wouldn’t benefit from standard treatments. If DBS becomes available as a treatment for people like them, it could have significant advantages. “Even some improvement in motor function could significantly improve quality of life,” said Tomycz, noting a range of benefits associated with improved mobility, including independence, cardiovascular health, and preventing dementia. The World Health Organization estimates that there are over 15 million people living worldwide with some form of spinal cord injury.

The team plans to continue safety and efficacy studies with more human patients, said Asboth, and test how patients could benefit from hybrid therapies that use DBS in conjunction with other neuromodulation techniques, such as spinal stimulation. Future research could also use the framework the group established to identify new brain regions related to other disorders.